LAND REPORT: East 8

Land Report Collective

About the exhibition

The Land Report Collective deals with landscape in fundamental ways and as a foundational reference point. Although each artist investigates formal and conceptual issues based on the landscape as an individual, the essence of our collective lies in the intersection between the things each of us point at – as if we were pointing to locations like road signs. New meanings and contexts emerge when viewers see the conversations that open up between works in an exhibition that would not normally occur when pieces are exhibited in isolation. Furthermore, the development of the work for each exhibition is a result of the artists being in direct and indirect dialogue with each other, the spaces they inhabit, and the people they interact with there. Through this active process, members of the collective make new work as if it were a conversation, even though each artist acts autonomously and there is no hierarchical structure imposed.

https://landreportcollective.com

Featuring:

Leticia R. Bajuyo www.leticiabajuyo.com

Jason S. Brown www.jasonsheridanbrown.com

Brian R. Jobe www.brianjobe.com

David L. Jones www.davidlawrencejones.com

Patrick Kikut www.patrickkikut.com

Shelby Shadwell www.shelbyshadwell.com

This exhibition is a collaboration between Buckingham Companies, CityWay and 60 on Center.March 18 through November 6, 2022

please call 317.624.8200 for public availability when not closed for private events

CityWay Gallery

at the Alexander Hotel

216 E. South St.

Indianapolis, IN 46204

Admission is free

Leticia R. Bajuyo, Hypergrass Landscapes, 2022, Artificial turf, wood, and adhesive. Bajuyo’s drawings, sculptures, site-specific works and large-scale installations highlight the impact of desire and the machines that create more desire. While these abstract patterns are aesthetically pleasing they reference the often frustrating and continuous re-arbitration that comes with homeownership. Using artificial turf in this series of landscapes, the artist’s critical vision questions societal norms of lawn care and our comfort, containment, and control of nature in the pursuit of a “well-manicured lawn.” Acknowledging that the American dream of homeownership is sugar coated, the artist is commenting on the joy and repulsion of our society’s obsessive struggle with nature and our neighbors that is cyclical.

Brian R Jobe, Right Angle Reply (Indianapolis), 2022, Brick and paint. Focusing on sculpture, installation, and public art, Jobe’s work is at the intersection of design and architecture where the delineation of pathways, borders and boundaries become interactions. Here the artist is drawing spatially by tracing of the angles and boundary of the wall. This work is stacked, held in compression without the use of hardware or adhesives. The use of construction grade materials gives structure, permanence, and gravity to the design in both the physical object and the space created between the wall and the bricks.

Brian R Jobe, Right Angle Reply (Indianapolis), 2022, Brick and paint

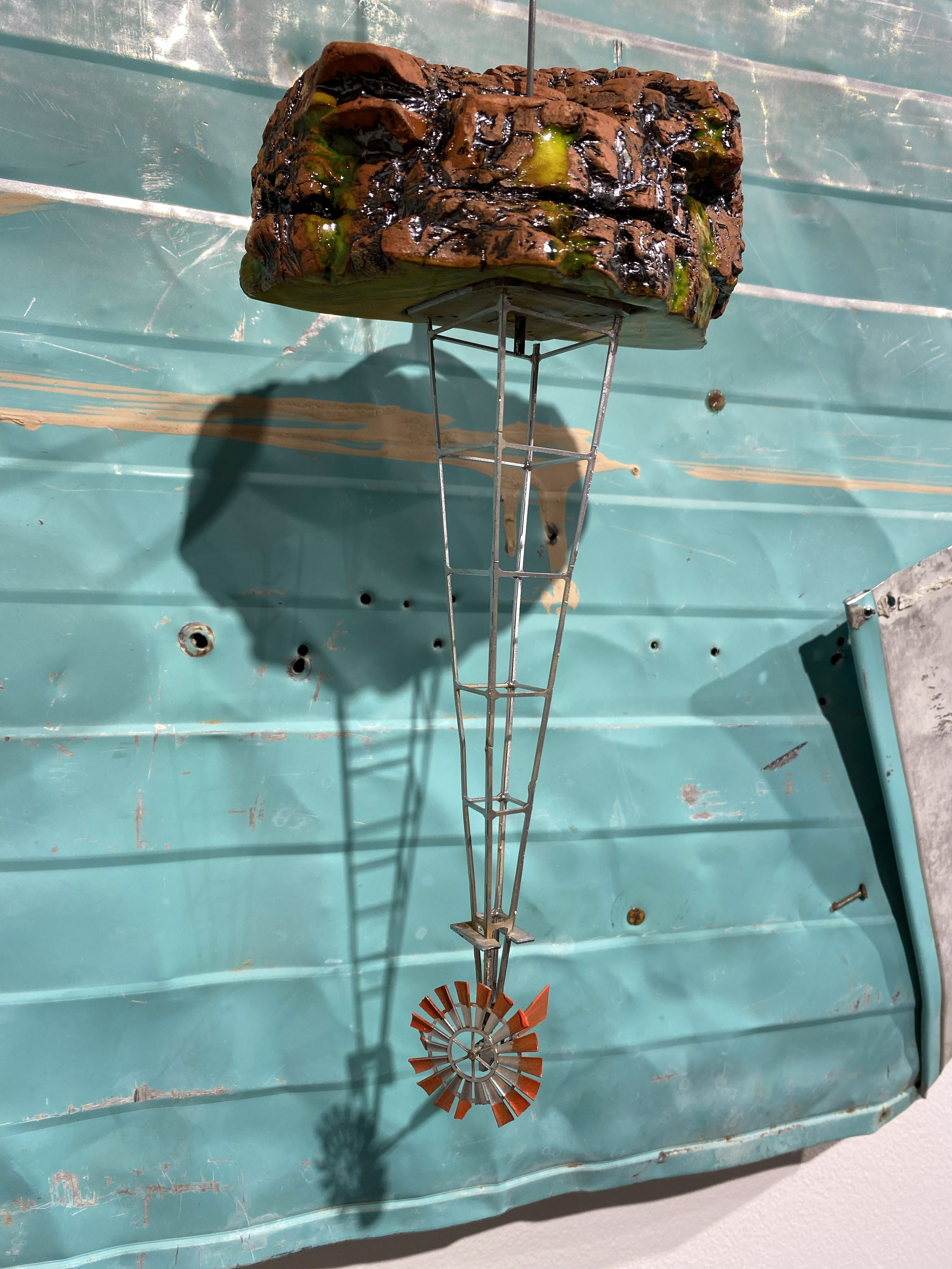

David L. Jones, Ode to Wyoming’s Boom and Bust Cycle, 2022, Found objects, cast aluminum, cast bronze, and model components. Jones is fascinated with the ever-present energy economy in the American West where pump jacks, well pads, pipelines, open pit coal mines, and uranium mines proliferate the landscape as a glaring reminder of our absolute dependence on fossil fuels. In 'Shirley Basin' and 'Ode To Wyoming’s Boom And Bust Cycle,' Jones cast and arranges objects as reminders to the reality of boom and bust cycles resulting in ghost towns. These arrangements memorize this cycle of rapid increase of activity followed by a rapid decrease of business, which in Wyoming, the tenth largest but least populated state, goes unnoticed because of its sparseness. Ghost towns, whether old or recent, are a direct effect of boom and bust as are remnants of fossil fuel extraction. The artist is interested in the cautionary story they tell about economic forces and the human condition. As Jones states, “Because much of the extractive industry happens in remote areas of this state, when you happen upon it, it often feels as if civilization has ended and this industrial equipment is all that’s left. While of course this isn’t the case, I’m often left wondering that if another civilization came along and happened upon this, what would it tell them about us as a society?”

David L. Jones, Shirley Basin, 2022, Found sheet metal, ceramic, model components, and lawn flag

David L. Jones, Shirley Basin (detail), 2022, Found sheet metal, ceramic, model components, and lawn flag

Jason S. Brown, Fractured Landscape 1, 2022, Steel. Using sculpture, performance, and installation, Brown engages in dialogue about individual, community, and place by examining human relationships with the natural world. In Fractured Landscape #1 and Fractured Landscape #2, beautiful geomatic abstract forms slowly reveal themselves as topographic maps of Appalachian Mountain ranges transformed by coal mining and mountaintop removal. This type of mining removes the summit in order to access the buried coal seams forever altering these natural formations. Here mountainous landscapes are replicated in jagged, geometric shapes producing forms reminiscent of satellite imagery and map programs, like Google. This series further’s Brown conversations exploring transitional post-industrial spaces where growth and decay are happening simultaneously and the impact that extractive industries such as mining, oil and gas have on the ecosystems and watersheds of Appalachian landscapes.

Jason S. Brown, Fractured Landscape 2, 2022, Steel

Leticia R. Bajuyo, Hypergrass Runner: Checkerboard, 2022, Artificial turf, tarp, adhesive, bungees and hardware. In this series of site-sensitive installations, Bajuyo creates a multi-layered experience highlighting impact of desire, re-arbitration of value and our romantic but often dangerous relationship with nature. The artist uses artificial turf to question our obsessive and repetitive pursuit of a “well-manicured lawn” and desire to contain nature. Supporting these mosaics is a commonly used blue tarp, which has become symbolic of natural disasters like hurricane and tornadoes for its use to shield or protect desired items from natural elements. This inexpensive and easily discarded material creates a danger for the natural environment. This conflicted argument of nature versus plastic is echoed in the tension of the bungee cords stretching this material toward itself.

Leticia R. Bajuyo, Hypergrass Runner: Diagonals, 2022, Artificial turf, tarp, adhesive, bungees and hardware

Leticia R. Bajuyo, Hypergrass Runner: Maze, 2022, Artificial turf, tarp, adhesive, bungees and hardware

Shelby Shadwell, SPACE BLANKET 6, 2022, Charcoal, pastel on polyester. This charcoal and pastel drawing is of a space blanket, known as a solar, emergency or thermal blanket, which is made of a compact lightweight material used to regulate the temperatures of things like spacecrafts and human beings. While often packed in first aid kits, these blankets have more recently become a symbol associated with the border crisis between the US and Mexico. Commonly featured in the media wrapped around migrants detained in camps where conditions are harsh, Shadwell’s hyperrealistic drawings lovingly recreate the blanket’s alluring metallic surface while referencing this struggle of land and ownership.

Shelby Shadwell, SPACE BLANKET 7, 2022, Charcoal, pastel on polyester. Shadwell is known for making large-scale hyper realistic charcoal and pastel drawings. For this series, Shadwell reproduces images of space blankets, a cheap and flimsy material with a brilliant sparkling appearance reminiscent of precious stones or metals. This metallic quality is directly in juxtaposition to its monetary value, not unlike “fool’s gold”. These metallic blankets are similar to materials found at a crash site near Roswell, New Mexico in 1947 and they allude to a shared cultural fascination with space travel and the possible existence of extraterrestrial life.

Shelby Shadwell, Untitled (anthracite coal), 2022, Charcoal, pastel on polyester. Shadwell made this drawing from the coal specimen located on the opposite wall of the gallery. Continuing themes from previous bodies of work, like the Space Blankets series, Shadwell focuses on the metallic luster which can be reminiscent of pyrite or “fool’s gold.” Through the grand reproduction of this specimen’s folds, cracks, and contours, the artist has created a fictional landscape.

Patrick Kikut, Colorado River Produce in Mobile Research Studio (MRS), 2021, Oil on Canvas. This series of still life paintings feature food produced by Colorado River Basin agriculture consumed throughout the nation and world. The millions of years old Colorado River does not reach its natural ending point in the Sea of Cortez, Mexico because humans have altered its flow to serve 40 million people in the Southwest and sustain agriculture along its sunny banks. As Kikut states, “I see this work as a reminder that we all are complicit in the fact that the river does not reach its natural end in the Sea of Cortez. We sacrifice the river for our melons, microgreens, peaches, citrus, peppers, and, alfalfa to feed cattle that are then sacrificed for burgers.” These still life paintings have become landscape paintings as they tell the story of this watershed.

Patrick Kikut, Colorado River Products/Green Chili Cheeseburger and Coors Light, 2022, Oil on Canvas

Patrick Kikut, Colorado River Produce on a Cardboard Box, 2021, Oil on Canvas

Patrick Kikut, Colorado River Produce/Map, 2020, Oil on Canvas

Patrick Kikut, Sacrificial Still Life: Lower Basin Produce-Mellons, Citrus, and Strawberries, 2021, Oil on Canvas

Patrick Kikut, Sacrificial Still Life: Upper Basin Produce and 18 inch Smoked Brown Trout, 2016, Oil on Canvas

Patrick Kikut, Sacrificial Still Life: Lake Mead Produce, 2022, Oil on Canvas

Patrick Kikut, Sacrificial Still Life: Lower Basin Fruit Stand, 2022, Oil on Canvas